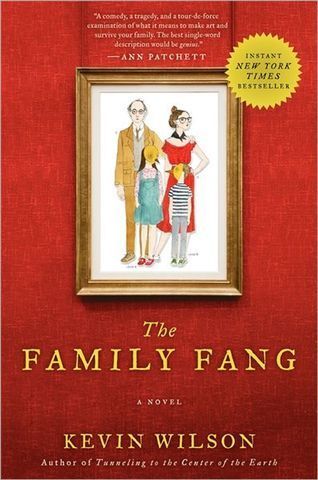

The Family Fang by Kevin Wilson begins with the line, “Mr. and Mrs. Fang called it art. Their children called it mischief.”

Preceding that are two quotes, the first:

It is grotesque how they go on

loving us, we go on loving them

The effrontery; barely imaginable,

of having caused us. And of how.

Their lives: surely

we can do better than that.

- WILLIAM MEREDITH. “PARENTS.”

And the second:

“It wasn’t real; it was a stage set, a stagy stage set.”

- DOROTHY B. HUGHES. IN A LONELY PLACE.

Smith’s novel, about the relationship of the individuals of a family – parents Camille and Caleb Fang and their children, Annie (Child A), and Buster (Child B) – is complicated by the fact that Mrs. and Mr. Fang are performance artists, and they routinely use their children in their art. After a colleague and mentor of the Fangs tell them that “children kill art,” a pregnant Camille and her husband determine instead that having children may instead create the opportunity to make new art.

The novel is told half in real time and half in a retrospect of Camille and Caleb’s documented works of performance art, self-containing stories in themselves that have a very clear beginning, middle, and end. One of these contains the documentation of a performance in which Annie and Buster pretend to busk in order to raise money for an operation for their fictional family dog. They sing songs that are intentionally awful, and a crowd, there half for sympathy and half for the spectacle, form around them. Caleb and Camille plant themselves as strangers to their performing children and yell things like, “YOU SUCK!” and “I HOPE YOUR DOG DIES!” in order to create something for the crowd to react to. When the family does their rendezvous in a park after the scene, Caleb sports a black eye from a punch that has also destroyed the camera concealing in his eyeglasses. But the performance is deemed an overwhelming success and creates a moment at the end of it where the Fangs seem more like a family than ever.

These documentations are interspersed with the real-time adult lives of Annie and Buster, who are dealing with the implications of a childhood submersed in art, and an adult life dealing with the experiences created by their parents. Annie, a successful artist, and Buster, a journalist for a men’s magazine, both find themselves reluctantly homeward bound after personal breakdowns in their professional lives. However, after moving back in with their parents, Camille and Caleb disappear, their abandoned van found mysteriously by the side of the road, surrounded by blood. Although Annie and Buster insist to the police that this is just another one of their parents’ performances, a series of similar abductions reported in the area again blur the lines between art, reality, truth, and fiction, and Annie and Buster find themselves on a journey to draw their parents out of hiding, or else to come to terms with their deaths.

Smith’s novel provides an excellent fictionalized discussion on art and its many forms, and how it can so effectively mimic and create life, and he sends Annie and Buster to investigate the ways these influences are felt.