It has taken me longer than it should have to get around to

reading Walter Dean Myers’ Monster. I

was recently doing some research on young adult books that combine both text

and image, and Monster was referenced

a few times because of the black and white photographs interspersed throughout.

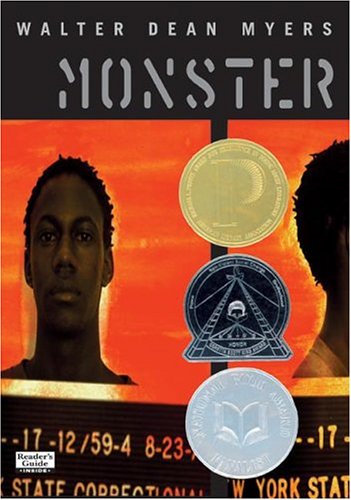

Monster won the first Prinz Award

when the award was created in 2000, and the experimental and challenging format

it engages with represented the kind of book that the Prinz Award wanted to

recognize.

Monster uses a

screenplay format to tell the story of Steve Harmon, a sixteen-year-old boy who

is on trial for the murder of a man, Alguinaldo Nesbitt, who owned a drug store

in Harlem. Harmon is implicated in the crime by a series of criminals who are

trying to lessen their sentences by cooperating with the police. On trial,

awaiting his sentencing as the “look-out” in the hold-up, Harmon writes his

story in screenplay form, his interest in films becoming more apparent as the

novel progresses. The screenplay is

interspersed with journal entries, as Harmon must return to his prison cell

during the downtime of his trial.

As a sixteen-year-old in jail, Harmon is in a constant state

of fear and anxiety. He begins his narrative by writing, “The best time to cry

is at night, when the lights are out and someone is being beaten up and

screaming for help. That way even if you sniffle a little they won’t hear you.

If anybody knows that you are crying, they’ll start talking about it and soon

it’ll be your turn to get beat up when the lights go out.” He has been in jail

for “a few months” but is not nearly close to getting used to the routine of

imprisonment. He decides to record the trial as a screenplay, since he has been

involved in a film club at his school and views the world through camera

angles, close-ups, and voiceovers. He is also writing as a way of

self-definition, particularly to find out who is his and what he has done. He

writes of his story, “I’ll write it down in the notebook they let me keep. I’ll

call it what the lady who is the prosecutor called me. Monster.”

The reader is introduced to the prosecutor, the defense, the

judge, and the jury. They are a dramatic list of characters at the beginning of

the screenplay, followed by the opening credits that Harmon figures to the

style of Star Wars, an indication of

both his age and interests. Spliced between the real-time trial are scenes that

attempt to carve out Harmon’s character: him and his younger brother Jerry

talking about superheroes; his film class; his friends.

There are also black and white photographs throughout, all

of them apparently of Harmon. The lack of color functions as a means of reading

Harmon’s trial as subsisting in a morally grey zone; his innocence is not so

black and white as the portrait photographs that appear in the book. Harmon

grapples with his participation in the holdup; even though he was just the

look-out, casing the drug store and making sure there were no obstacles in the

way, Nesbitt still was murdered. He talks to other prisoners in jail who take

responsibility for their crime, anticipating “guilty” verdicts and connecting

them innately to the crime they committed. Harmon, however, is different. He

can’t grapple with the moral uncertainty of his crime. He didn’t pull the

trigger, but he was involved, even peripherally, in murder. He represents the

facts of the trial in an unflinching account of witnesses and cross-examinations,

but there is still a sense of uncertainty about what Harmon’s verdict will be,

and his own moral dilemma.

As the book neared the end, I was actually getting worried

that the verdict wouldn’t be revealed, and that Myers’ would leave the novel

hanging on the same uncertainty that threads throughout the story. Luckily, there

is no such ambiguity, although I’m not sure if this does anything to lessen the

uncertainty, or Harmon’s own sense of morality and accountability. The last few

lines of the book hold the reader in a sense of ambivalence, as Harmon

struggles to define who he is: “I want to look at myself a thousand times to

look for one true image. When Miss O’Brien looked at me…what did she see that

caused her to turn away? What did she see?”

I would not recommend leaving Monster unread. For its innovative form, its ambiguous subject, and

Harmon’s unflinching voice, it is certainly a book worth reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment